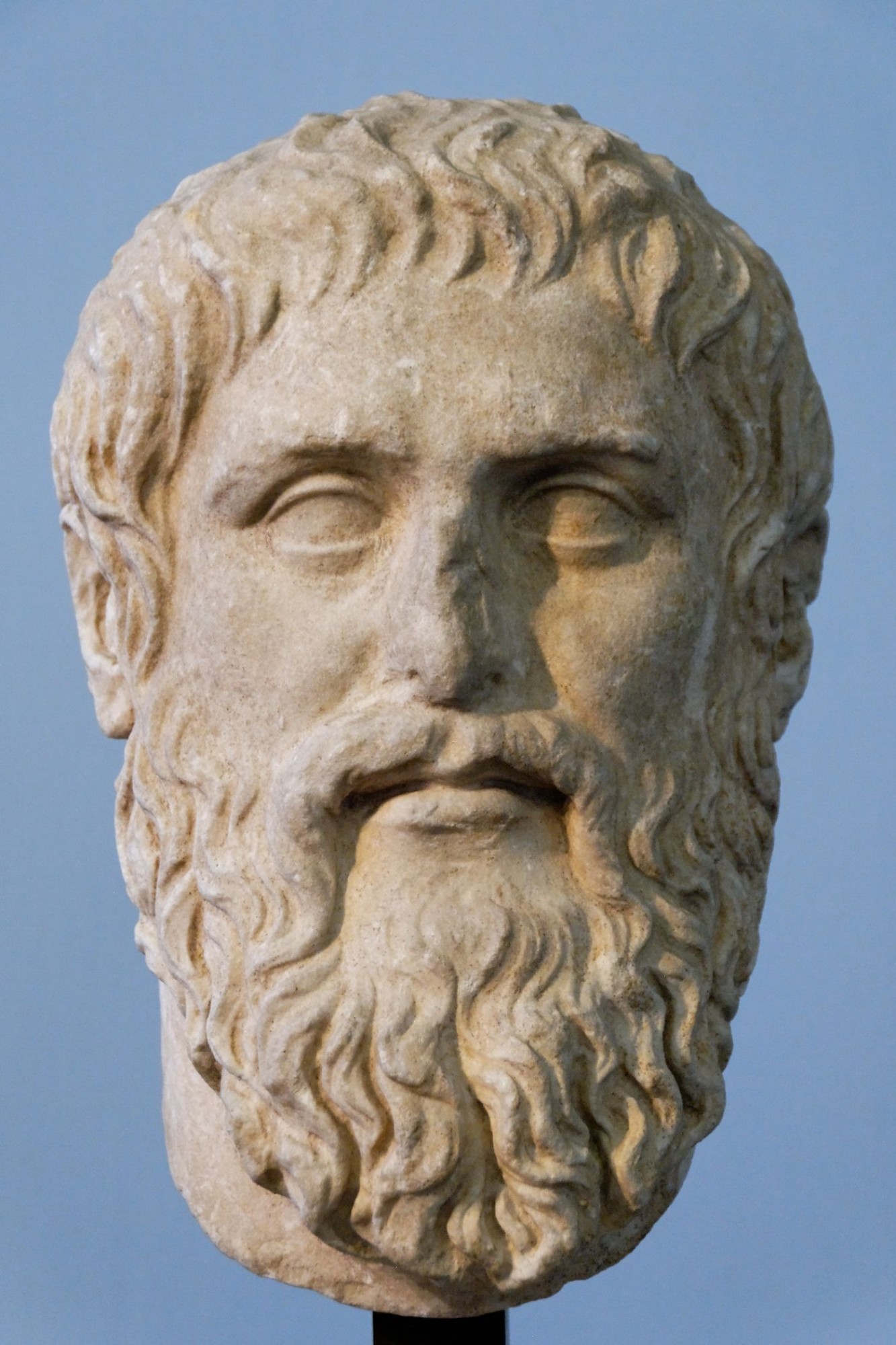

Plato

Plato's Views and Opinions on Reality and Ideals

Plato, a foundational figure in Western philosophy, was a student of Socrates and teacher to Aristotle. His ideas have profoundly influenced the intellectual traditions of the West. His dialogues, still widely read, explore the perpetual quest for wisdom and the complexities of life. Plato's examination of ethical and moral thought, through deeply engaging texts, continues to resonate in contemporary discussions on morality and justice.

His philosophical work extends into political theory, where he considers the structure of an ideal state—a subject that aligns closely with his ethical views. In "The Republic," Plato reflects on questions of justice and the ideal society, presenting the concept of philosopher-kings as governors of a just city-state. His thoughts embrace an investigative approach to knowledge and truth, moving beyond the sensory experience to ideas of immutable forms.

Summary

- Plato's work is essential to the foundations of Western philosophy.

- He examines moral and ethical concepts, often using dialectics.

- Plato's influence stretches from political philosophy to notions of justice and truth.

The Life of Plato

Plato's contributions to philosophy are deeply rooted in his life experiences and the societal structures of ancient Greece. His encounters with Socrates and his establishment of the Academy are pivotal to his story.

Early Years and Influences

Born into an aristocratic family in Athens, Greece, around 428 or 427 BCE, Plato was poised for a life of political engagement and intellectual rigor. His early years were shaped under the shadow of the Peloponnesian War, a defining historical context that influenced his later philosophical endeavours.

As a young man, Plato found a mentor in Socrates, whose method of questioning and virtue ethics deeply affected his own philosophical outlook. Plato was among the youths Socrates was accused of corrupting, a charge that led to Socrates' eventual execution and a turning point in Plato's life.

Plato's Travels

After Socrates' death, Plato traveled extensively, absorbing various philosophical influences. These journeys led him to places like Egypt, Italy, and potentially even as far as Libya and Syria. His travels provided him with a broad range of knowledge and an exposure to different cultures and ideas, which later became instrumental in his philosophical works.

Founding the Academy

Upon his return to Athens, Plato founded the Academy, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. This establishment not only educated future statesmen and philosophers but also served as a haven for intellectual development. The curriculum combined mathematics, philosophy, and scientific inquiry, laying the groundwork for future educational institutions. Plato's time in Syracuse, Sicily, also reflected his ongoing real-world interests, as he sought, albeit unsuccessfully, to apply his political theories in practice by advising the ruler Dionysius the Younger.

Platonic Philosophy

Plato's philosophy is a monumental framework that integrates his vibrant metaphysical principles with profound ethical implications. It embraces the quest for ultimate truth, a reality beyond the physical world, and the pursuit of knowledge through dialectical reasoning.

Theory of Forms

Plato's Theory of Forms posits that non-material abstract Forms, or ideas, represent the most accurate reality. He believes that these Forms are eternal and unchangeable, standing in stark contrast to the material objects we encounter, which are mere shadows of their perfect counterparts.

Although the material world is subject to change and decay, the Forms are permanent and constitute true reality—a concept central to his metaphysical understanding. For instance, when Plato discusses the nature of beauty, he is not referring to a beautiful object in the sensory world but to the immutable Form of beauty itself, an idea that defines the essence of beauty in all manifestations.

Encapsulating this metaphysical vision, Plato also mused on what truth means, suggesting that our sensory perceptions often deceive us, and only through rational thought can we approach the truth reflected in the Forms.

Knowledge and Epistemology

Underlying Plato's philosophy is a rigorous epistemology—the theory of knowledge. He argues that knowledge is not derived from sensory experience but recollected through reasoning and intellectual intuition.

Plato maintains that this is because the soul, before its incarnation in the body, was in the realm of Forms where it directly apprehended the Forms.

True knowledge, then, is the intellectual apprehension of the Forms. In the pursuit of knowledge, Plato's tool of choice is the dialectic, a method of inquiry that, through structured conversation and questioning, enables individuals to rise from the illusion of the senses to the illumination of intellectual insight.

The dialectic is not just a method of debate but a pathway to illumination—a journey from the shadows of ignorance to the brightness of philosophical understanding.

In the space of dreams, the exploration of deeper realities blurs, according to Plato, the line between illusion and authentic desires, presenting a unique and complex dimension of human cognition that intersects meaningfully with his overarching philosophy.

Ethical and Moral Thoughts

In Plato's philosophy, ethics form a core component of how humans should live and interact within society. His arguments revolve around the interplay between individual virtue and collective justice.

Virtue and Goodness

Plato saw virtue as the foundation of a good life. He postulated that virtues, such as wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice, were forms of goodness that individuals could cultivate.

For Plato, the attainment of virtue was tied to the soul's quest for knowledge, positing that true understanding leads to moral behavior. He also discussed the role of empathy as a social bond that underlines moral clarity in his dialogues.

Justice and State

Central to Plato's ethical thought is the concept of justice, which he explores intricately in his work "The Republic." He proposes that a just state mirrors a just individual, where each class performs its role harmoniously.

Plato's musings on justice reflect the intricate relationship between the individual's moral conduct and the ethical structure of the state. He also addresses the intricate blend of inherent qualities and life experiences, emphasizing the state's role in shaping these through education.

Socratic Ethics

Underpinning Plato's ethical framework are the Socratic ethics that focus on self-knowledge as a critical component of virtuous living. Socratic ethics places a premium on understanding one's own human nature, which is a prerequisite for achieving happiness and virtue.

Plato's deep dive into human nature suggests that virtue is both an expression of our innate qualities and the culmination of our life's experiences.

Political Philosophy and Society

Plato's political philosophy ventures deep into the structure of society and the ethical implications of government. His work in "The Republic" remains a cornerstone of Western political thought, with a special focus on the role of justice in politics.

The Republic and Kallipolis

In Plato's envisioned state of Kallipolis, or the ideal city, justice and the common good are the cornerstones. He constructs a society with a rigid class system based on the innate qualities of individuals, where the Guardians (philosophers and warriors) are distinct from the producers (farmers, artisans, etc).

Through Plato's detailed on education in the Republic, it's evident he views a well-ordered society as one educated and structured to reflect the Forms, particularly the Form of the Good.

Critique of Democracy

Plato's critical assessment of democracy stems from his belief in its inherent instability and tendency to fall into tyranny, due to what he saw as excessive freedom. He argued that democracy often leads to the election of leaders who are unfit, driven by their desires rather than the common good, resulting in a political system that's flawed and vulnerable.

Philosopher-Kings Concept

The concept of the Philosopher-King is central to Plato's vision of a perfect government. He posits that only philosophers, who seek knowledge and truth, are fit to rule because they have the ability to comprehend the Forms and the Form of the Good.

Plato's ideal was for leaders to be virtuous and wise, ruling not for personal gain but for the benefit of the entire state—a stark contrast to the oligarchies and aristocracies of his time.

Dialectics and Dialogues

Plato's philosophy was fundamentally rooted in the practice of dialectical method and the execution of dialogue. His approach involves a systematic questioning to elucidate ideas and challenge preconceived notions.

The Art of Dialogue

In the eyes of Plato, dialogue is not merely a form of conversation but a rigorous method for achieving philosophical truth. He saw the dialectic as a structured process where a philosopher, like Socrates, engages with interlocutors to dissect and examine beliefs, aiming to reveal contradictions and arrive at a deeper understanding.

This process often begins with Socratic questioning, aimed at drawing out a person's understanding and driving inquiry deeper.

Major Platonic Dialogues

Plato is renowned for his many written works, with the Republic and Symposium being among the foremost. Within these dialogues, characters like Socrates expound on various philosophical themes through conversations with other figures.

The Republic delves into justice and the ideal state, while the Symposium explores the nature of love. Other significant works include the Parmenides, with its abstract treatment of the forms, and the Meno, which investigates virtue.

Character Development

Character development is a subtle, yet crucial, element within Plato's dialogues. For example, through the narrative form, Socrates emerges not only as a philosopher but also as a mentor and intellectual provocateur.

The development of characters such as the young Theaetetus in the dialogue of the same name illustrates the transformative impact of Socratic dialogue, as it shapes the minds of Plato's interlocutors and, by extension, the reader.

Platonic Influence and Legacy

The philosophical framework set by Plato has left an indelible mark on Western thought. From the establishment of the Academy to his profound impact on his own pupils and beyond, his legacy has played a crucial role in shaping philosophy and education.

Impact on Western Philosophy

Plato's contributions to Western philosophy are immense, having developed vital areas such as epistemology, metaphysics, and ethics. His dialogues, which often featured Socrates as a character, laid the groundwork for philosophical inquiry.

His idea of the world of forms, as being distinct from the reality experienced by our senses, continues to be a foundational concept in philosophy.

Plato's method of exploration, via Socratic questioning, encouraged a critical approach to reason and understanding. This technique fostered an environment where ideas could be examined deeply, which has been integral to the development of Western thought.

Plato's Students and Successors

Among Plato's students, Aristotle stands out as the most prominent. Aristotle would go on to challenge many of Plato’s teachings. However, his work was largely informed by the time he spent at the Academy. Plato founded this institution for education and philosophy.

The differences between Aristotle and Plato's philosophies became a driving force behind the evolution of philosophical interpretation and inquiry. Such robust scholarly debate encouraged further progress in philosophical thought.

Platonism through History

The term ‘Platonism’ has come to describe the philosophical doctrines closely associated with Plato and his dialogues. Throughout history, this school of thought has been revived and reinterpreted, influencing various areas like mathematics, metaphysics, and even Christian theology.

The legacy of Plato is such that centuries after his passing, Platonism still provides a crucial framework for the contemplation of existential questions and influence on the modern philosophical landscape. His work continues to be a significant point of reference for contemporary philosophers.

Plato's Academy would not only educate his immediate successors but also serve as a model for future institutions, thus solidifying Plato's role as a pivotal figure in the Western educational tradition.

Art, Poetry, and Aesthetics

Plato's critical eye cast over the world of art and poetry sought to understand their impact on society and individuals. He was deeply concerned with how they related to concepts of beauty, truth, and reality.

Plato's Views on Arts

Plato had a complex relationship with the arts. He saw them as a form of imitation that could influence one's character and societal order. Artistic endeavors, especially theatre and music, were more than mere entertainment to him; they were tools that held the potential to shape the moral fabric of a civilization.

By imitating forms, he believed that arts could both reflect and distort the ideal Forms, which were the truest representation of reality. In examining Plato's perspectives on the theatre, it becomes evident that while he recognized the emotional appeal of plays, he was wary of their potential to lead audiences away from the pursuit of the good by presenting imitations rather than truths.

Beauty and Aesthetics

Beauty for Plato was intimately connected with the notion of the Forms. It's in the Symposium where Plato unpacks the idea that beauty is an eternal Form at a higher level of reality than the physical objects that only appear beautiful.

Beauty and aesthetics, in his view, were not just about visual appearance but were more deeply tied to the truth and intrinsic goodness of the ideas they represented. This is why beauty was so important: by appreciating pure beauty, one could gradually ascend to understanding and embracing the form of beauty itself.

However, the appreciation of beauty in art or poetry had to be carefully navigated, as Plato also recognized how easily one could be enamored by mere appearances, mistaking them for the reality of the Forms.

Mathematics and Logic

Plato's philosophy of mathematics is a crucial lens through which he examines the forms, seeking knowledge beyond the physical world. Geometry and numeracy are not merely practical tools but pathways to understanding the truths of reality.

Plato's Mathematical Theories

Plato perceived mathematics as not just a discipline on its own but also a means of accessing higher truths. For Plato, mathematical objects such as numbers and geometric shapes exist in a non-physical realm, which he calls the world of Forms or Ideas.

These Forms represent the perfect, immutable concepts behind the imperfect, fluctuating phenomena experienced in the physical world. He famously inscribed above the entrance to his Academy, "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here," revealing his stance on the indispensable role of mathematics in acquiring real knowledge.

Mathematical pursuits, particularly geometry, were not just practical exercises but served as metaphors for Plato's understanding of the universe. The dodecahedron, for instance, was special to him, symbolizing the universe's overall structure—showcasing his deep intertwining of geometry and philosophical insight.

Influence of Pythagoras

The teachings of Pythagoras significantly impacted Plato. Pythagoreanism posited that numbers are the fundamental reality, providing a mystical dimension to mathematics.

It suggests that numbers and their relationships are not constructs but rather intrinsic truths that structure the universe. Plato adopted and expanded this viewpoint, proposing that mathematical relationships reveal the harmonious order of the cosmos.

For Pythagoras and later Plato, numbers were seen as key to unlocking the mysteries of the universe and achieving a true understanding of reality.

Both believed that the soul can rise to the communion with the Forms through mathematical philosophy, a process which aligns the soul with the truths of a higher, more perfect realm.

Plato's mathematical theories hence reflect a blend of Pythagorean influences with his own philosophical assertions. He believed that the pursuit of mathematical truth functions as a bridge between the sensory world and the eternal world of the Forms.

All articles

End of content

No more pages to load